How Rum Helped Canadians Survive the Trenches

From ancient Greece to the Viking era, European empires, and the First World War, soldiers were consuming alcohol for pretty much the same reasons.

Alcohol helps builds the “Esprit de Corps” amongst men, the sense of fellowship and common loyalty so important to an army. Socializing over wine, beer or spirits forges friendships, trust and a feeling of being in this together. On the battlefield, alcohol gives courage and raises morale. In the camp, it becomes a clean beverage that water can’t always provide. And once the battle is over, the alcohol is used to clean wounds or numb the mind of the unfortunates who must endure an operation with little to no anesthesia. Afterwards, alcohol often becomes the crutch to manage the traumas.

In the years preceding the First World War, the United States and Canada were entering an era of prohibition where no alcohol was allowed under any circumstance. How then, did Canadian soldiers survive the horrors of WW1 and the trenches?

The French army had their “Pinard,” a daily ration of usually mediocre wine that nonetheless kept the “poilu” (a moniker used to describe the common soldier) going. They were issued 1⁄2 a litre per day, more immediately before a battle or after if the number of casualties had been particularly high.

The Germans also had their daily rations of alcohol, which would vary depending on where they were. In beer-producing regions, beer would be served. In the wine-producing region, likewise. Sometimes, the rations would be particularly generous, especially when conquering a wine region or coming across wineries or distilleries.

Meanwhile, the American soldiers could only look on and drink water or tea. The temperance movement in the United States was so powerful, and their propaganda so effective that commanding officers had to enforce dry rules amongst their ranks. By and large, they were successful at controlling the soldiers and at convincing them that evil would ensue if they succumbed to the drink. However, off duty, these high morals quickly failed the soldiers’ resolve. Away from the tranches and the commanding officers, the American soldiers quickly learned the European ways and developed a taste of the local drinks and lifestyles. In fact, the American soldiers that were lucky enough to return home after the war are credited for bringing back a liking for wines and spirits that later on helped propel the American wine industry once prohibition ended. But that is another story.

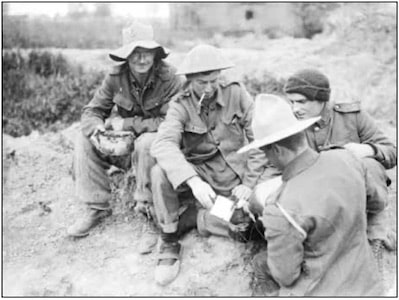

The Canadian experience differed from that of the Americans. Canada joined the war efforts under the British banner alongside other countries such as India, Australia, South Africa and Ireland. Under this arrangement, Canada was free of the constraints experienced by their southern neighbours and obligingly yielded to the local customs. They gratefully received their daily rations of Rum issued by the British army. Thus, Rum became a staple of the Canadian soldier’s war experience. In a September 2002 article published in the Legion Magazine, Tim Cook quotes WW1 Canadian Infantryman Ralph Bell who wrote:

“When the days shorten, and the rain never ceases; when the sky is ever grey, the nights, chill, and the trenches thigh-deep in mud and water; when the front is altogether a beastly place, in fact, we have one consolation. It comes in gallon jars, marked simply SRD.” That SRD was army- issued Service Rum Diluted or Special Red Demerara…”

Life was hellish in the wasteland of the trenches for the thousands of young Canadian soldiers – men wading in cold mud, sleeping with rats, lice and corpses. In these conditions, a soldier’s pride, fear and sense of mission was not enough to keep him going. The daily Rum – 1/16th of a pint of over-proofed thick dark Rum (along with the infrequent family parcels of foods and sweets) played a crucial role.

Cook describes the daily routine; “Rum was initially given to men at the dawn stand-to and stand-down at dusk. As these were the expected times for an enemy attack, the whole forward unit was called out with rifles at the ready. If an attack came, sergeants doled out two ounces of the overproof Rum to each man. The practice of stand-to faded out in the second year of the war when both sides were aware that the other was on high alert, but the rum ration remained.”

The rum ration played such an essential role in the men’s daily life that the threat of skipping a ration of alcohol was enough to instil discipline among them. Conversely, extra rations would be given as rewards to the men who volunteered to do strenuous tasks, rescue fallen soldiers in “no man’s land”, or take on patrolling or raiding duties. The wounded would also be given a shot of Rum to lessen the pain or as a last consolation before they died.

You may wonder why Rum was used rather than whisky, beer, gin or vodka. The answer is simple. All the grains, fruits and vegetables were necessary for the production of food. Sugar (usually molasses imported in barrel size) was the simplest and cheapest way to make spirits. Rum was also quick to make.

Some credit Rum as one of the key factors that helped the allies survive the horrors of war and keep them going. Others vilified it for sending back home soldiers with addiction issues. As we enjoy our incredible lifestyle, even through a pandemic, we are in no position to weigh in and judge. In truth, we can not even begin to imagine what the First World War soldiers experienced. We can only wish moments such as Remembrance Day will inspire us to find other ways to settle differences than by waging wars.

“ …The poor man lay at length and brief and mad Flung out his cry of doom; soon ebbed and dumb He yielded. Worley with a tot of rum

And shouting in his face could not restore him. The ship of Charon over the channel bore him. All marvelled even on that most deathly day

To see this life so spirited away.”

– Excerpt from “Pillbox” by Edmund Blunden, September 29, 1917