February is the month of love so I will share one of my loves, searching for galls. If you have not heard of a gall, then you have not yet come to appreciate how truly crazy relationships in nature can be. There are many galls out there, but today I will discuss only the pinecone gall made by a little pinecone gall midge or Rabdophaga strobiloides.

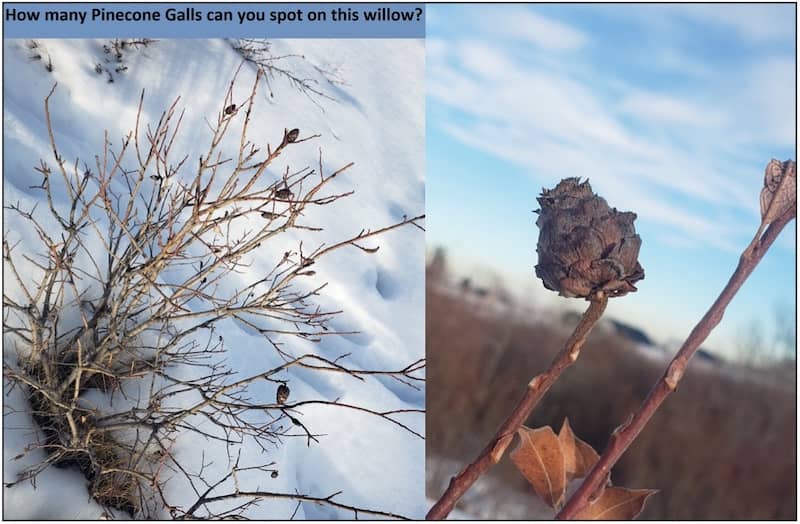

Winter is the best time to find these pinecone galls as the lack of leaves make branches more visible. Perhaps you are thinking, “but pine trees are conifers. They still have all their needles,” which is correct. However, the pinecone gall is named for its beautifully layered shape that resembles a pinecone, not for the location where it is found. To find these little treasures, head for a patch of willows (Bebb’s Willow is a favourite of the midges) and start scanning the bare branches for blobs at the tips. When you spot a blob take a closer look and see if it looks like a misplaced pinecone; if it does, congratulations you have found your first pinecone gall. If you had x-ray vision you would be able to see the small midge larva tucked into the centre of this masterpiece of a nursery.

How does the tiny adult pinecone gall midge create such a thing? Part of the mystery is that the female midge lays an egg at the end of a willow bud in late Spring. She introduces chemicals into the leaf tissue at the same time and the willow bud starts to grow abnormally, at first like a cluster of leaves, then into a ball shape, and finally the pinecone shape. The willow plant is the one doing all the building, not the midge, but as the plant is not killed by this gall it is called an inquiline gall. The egg hatches at the start of this process and the larva starts to feed on its ever-growing gall nursery. It would be like having edible walls in your room that expand as your appetite increases and become more insulated over time to protect you from the cold of winter.

If this nursery set up sounds cushy to you, you are not alone; there are several insects that agree. In Donald W. Stokes “A Guide to Nature in Winter” he mentions a study where 23 pinecone galls yielded 564 different insects from egg to adult in life stages. Some of these insects just share the many layers of the pinecone gall in a neighbourly way. Others, like wasps, have the “gall” to inject their eggs directly into the midge larvae, so that their young have a tasty baby midge as their first meal. Insect activity is seldom overlooked by those with a “bird’s eye” view. If you find a pinecone gall that looks like it has a hole in it chances are a bird took advantage of the insect buffet waiting inside these hospitable galls. If the midge larva avoids all of these hazards, then it will form a pupa in the gall and emerge as an adult midge in the Spring.

Nothing reminds me of how little we understand the complexity of nature quite like a gall, and just like a willow bud my heart has swelled to accept them and all of the mysteries they have to reveal.